ctronic assembly, solder joint quality directly determines product performance and reliability. A Cold Solder Joint (CSJ) is one of the most common defects affecting solder reliability. Unlike a merely visually imperfect solder joint, a cold solder joint fundamentally fails to form an effective metallurgical bond. Its consequences include intermittent contact resistance, poor connectivity, and structural failures, which are especially critical in high-reliability industries such as aerospace, automotive, and medical electronics.

1. Definition and Microscopic Nature of Cold Solder Joints

From a metallurgical perspective, solder joint quality depends on two core factors:

Wetting Behavior: Whether the molten solder can spread and cover the substrate surface

Intermetallic Compound (IMC) Formation: The metallurgical reaction between solder and substrate forming a stable bond

A cold solder joint occurs when solder does not adequately wet the pad or lead, or fails to form a continuous IMC layer, leaving non-wetted regions and poor metal contact at the interface.

Reference IMC thickness for typical lead-free SAC305 solder:

Condition IMC Thickness (Typical)

Good soldering 1.5 – 3 µm

Overheated/overexposed > 4 µm (can become brittle)

Cold solder joint < 0.5 µm (discontinuous)

As shown, cold solder jointsoften have IMC layers far below the reliable standard.

2. Causes: Thermal, Surface, and Chemical Factors

Solder wetting and IMC formation are influenced by three main factors:

2.1 Thermal Factors

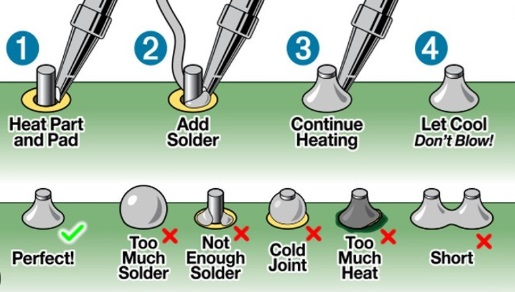

Whether the solder achieves sufficient wetting depends on heat input:

Soldering temperature below recommended levels

For lead-free SAC305, recommended reflow peak temperature: 235–245°C

Hand soldering iron temperature: 350–380°C

Insufficient heat transfer

Large copper pads or thick leads dissipate heat quickly, requiring higher heat input

Insufficient dwell time

Wetting requires time; removing heat too early prevents full spreading

Example data: In hand soldering, if the iron temperature is only 280–300°C, the wetting angle can rise to 80–90°, far above a good joint’s 20–30°, indicating insufficient wetting.

2.2 Surface Condition

Whether the pad/lead surface is clean and free of oxides is critical:

Surface Condition Wetting Angle (°)

Gold/Silver plating 20–30

Fresh OSP 25–35

Oxidized/contaminated >60

Wetting angles >60° make solder spreading difficult, often resulting in cold solder joints.

2.3 Chemical Factors

Solder and flux chemistry dictate wetting dynamics:

Active flux cleans oxides more efficiently

Solder composition (Sn-Ag-Cu ratio) affects surface tension

Degraded or contaminated flux increases wetting time

Experiments show that under degraded flux, wetting completion time can be 2–5 times longer, making standard heating insufficient for proper spreading.

3. Identification and Diagnosis of Cold Solder Joints

Relying solely on appearance is often inaccurate. CSJ diagnosis usually uses:

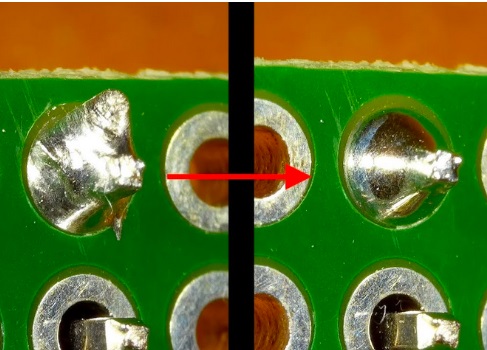

3.1 Visual Inspection (AOI / Manual)

Typical appearance:

Dull, matte finish

Solder appears grainy or separated

Edges irregular, uneven

Wetting angle criterion: wetting angle > 60° → possible cold solder joint

3.2 X-Ray / CT Inspection

Used to detect internal non-wetted regions:

Uneven solder fillet height

Hidden cold joint layers

3.3 Cross-section Analysis (SEM / EDS)

Microscopic examination is the most decisive:

IMC layer thin or discontinuous

Micro-cracks or voids at the interface

This micro-level evidence is the gold standard for identifying CSJs.

4. Effects on Electrical and Mechanical Reliability

A single cold solder joint can cause significant risks:

4.1 Increased Electrical Contact Resistance

Non-wetted interfaces produce poor connectivity:

Increased resistance

Signal integrity degradation, critical in high-frequency circuits

Experimental data:

Cold solder joint resistance is on average 5–15 mΩ higher than good solder joints, which is significant in high-speed, precision circuits.

4.2 Reduced Mechanical Strength

Discontinuous IMC layers make the joint prone to cracks under thermal cycling or vibration.

Thermal cycling tests show cold solder joints fail 2–10 times more frequently than good joints.

5. Process Measures to Control Cold Solder Joints

5.1 Standardize Soldering Thermal Profiles

For lead-free reflow:

Preheat: 150–180°C

Peak: 235–245°C

Cooling rate: 0.8–2°C/s

Time control is critical. Too rapid heating or too short dwell may prevent flux activation.

5.2 Improve Heat Transfer

For large pads or leads:

Use higher-power soldering irons (hand solder ≥40W)

Use plating and tools with better thermal conductivity

5.3 Optimize Materials and Flux

Use more active flux

Regularly replace solder wire to avoid oxidation

PCB surface treatment: ENIG / ImmAg for better wetting

6. Conclusion

A Cold Solder Joint is not merely a superficial flaw; it represents a solder that has not achieved critical wetting and effective metallurgical bonding. Its formation is influenced by thermal, surface, and chemical factors, and it significantly impacts electrical resistance and mechanical reliability.